BEFORE EXPLORING THIS FOLDER, I suggest that you review the folder Nathan Melvrie Workman & Juditha Totten Hamrick…(Historical Narratives Described).

Nathan Melvrie Workman & Juditha Totten Hamrick, 1877-1965 (Hollie Workman Interviews)

About This Folder:

This folder enumerates the interviews I had with Hollie Darius Workman, July 3, 2003. They were recorded at the annual Workman Family reunion, held near Eakle, on Robinson Fork, Clay County, West Virginia. Also included is a very brief interview with Alta Workman Brady.

More information (including maps and photos) about the 2001 family reunion is provided near the end of this folder.

Alta Workman Brady Interview

Before I interviewed Hollie, I was able to record a brief conversation with Alta (Hollie’s sister).

To hear Alta tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

AWBv1: Alta’s parents and where she grew up

Mike: Well, you grew up in that house right there, close to where you are living, right?

Alta: No, my mother, I suppose, did live in the log house that is there. But I don’t know, we lived in so many houses, I wouldn’t know how to tell you.

Mike: What do you remember about your mother and father?

Alta: Well, I remember they were hard workers, and they were good people. They taught us right from wrong…sometimes with a switch.

Mike: Did they take you to church?

Alta: Yes, they took us to church. They taught us how to work. Grew up and learned what it meant to make a living.

Mike: Where were you born?

Alta: Well, as near as I can tell you, up on the hill from Eakle. That is all I can tell you. Just out in the country.

Mike: So, you lived in this area all your life?

Alta: We lived in Ohio for a year. The rest of the time, we have lived in West Virginia. Mostly in Clay County.

Mike: Where are you in the family? There were 13 kids, right?

Alta: I am number nine. Brothers younger than me; I am the youngest girl.

Hollie Workman Interviews

My conversations with Hollie are organized by general topic. A table of contents is listed below:

• HDWv3: Holly’s recollection of his parents; living in rural Clay County

• HDWv5: Hollie didn’t know much about their ancestors

• HDWv5: Holly describes his mother’s and father’s educations

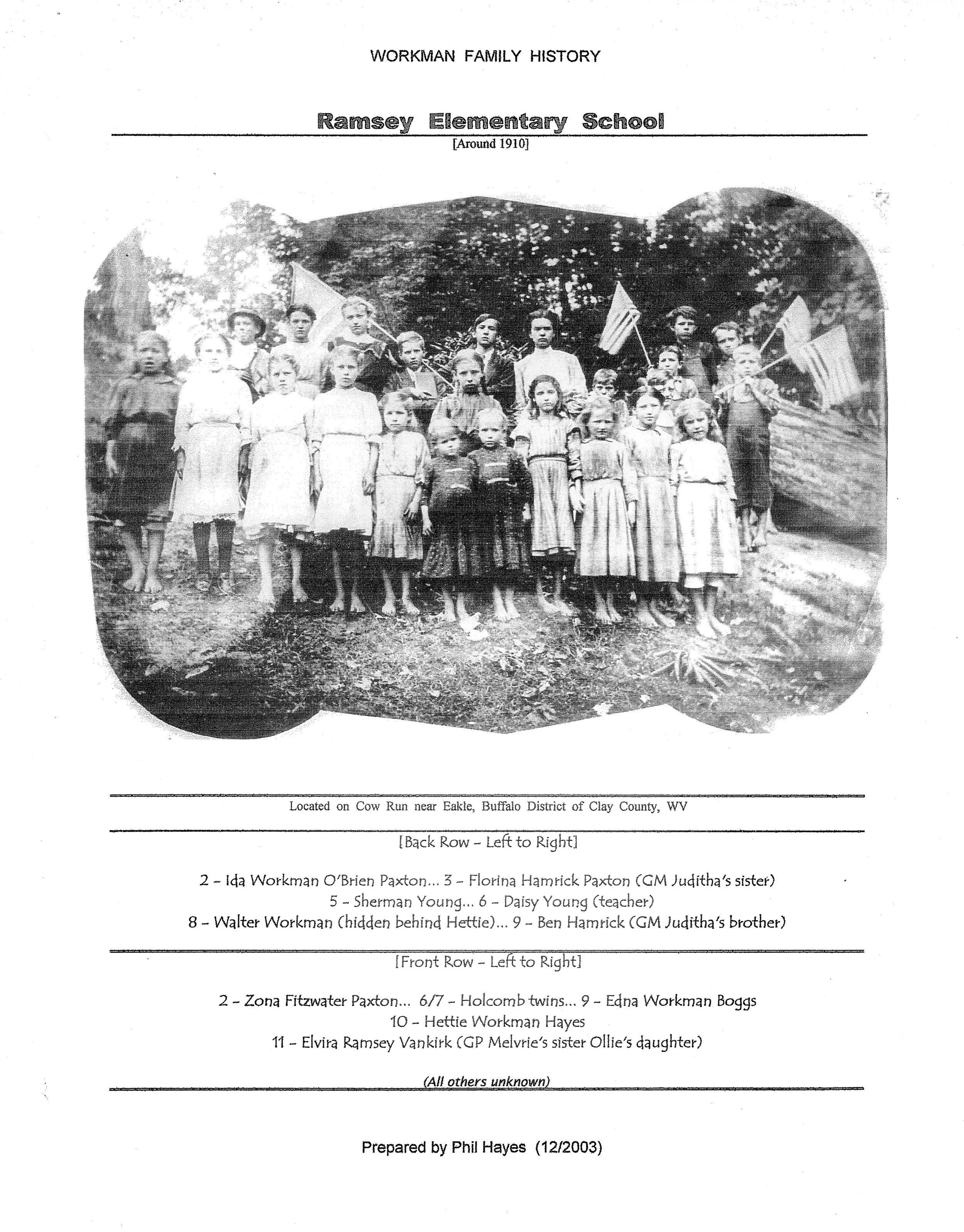

• HDWv5: Holly describes Juditha’s lineage; Ramsey Cemetery; where his siblings are buried

• HDWv5: Nathan Melvrie’s occupations

• HDWv5: Nathan Melvrie’s story telling

• HDWv5: No electricity, but a gasoline powered washing machine

• HDWv5: Hollie’s schooling

• HDWv5: Hollie worked on the farm and for other people

• HDWv5: Family recollections; courtship rituals

To hear Hollie tell a story, click the audio button. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

Hollie’s recollection of his parents; living in rural Clay County

Add photo of Antioch Baptist Church

-

Hollie: My name is Holly Workman, and I am the next to the last boy, living, for the old generation of [Nathan] Melvrie Workman family. I lived here for 78 year and then went to Florida to finish it up. I will probably come back, but it will probably be after I die. I don’t know whether or not I will, to tell you the truth. But there are so many things that you could mention that I don’t know which one to start with really.

My parents were just normal people, like you saw in that particular day and particular place. Honest, moral, back then their word was their bond, you know; you did not have to sign something to say I will do it. You trusted them to do it then. They were that type of people.

Mike: Were they Christians?

Hollie: They were both Christians and belonged to the Missionary Baptist Church.

Someone: Was that Antioch Missionary Baptist Church that we passed on the way?

Holly: Up here…and that is the church over there. And one thing I would love to mention about both of them…the one thing I mentioned about my mother is it was kind of usual at that time—every time after the initial introduction to each other, she would ask them if they had had their dinner or whatever meal it was close to. She always asked them if they had had a meal. If they said they hadn’t, she automatically went and started preparing them something. And then when they got ready to go home, she always had a bag of something ready for them to take home with them. Something maybe they did not even need, but she wanted to give it to them. She did it for everybody. It wasn’t just one. If there wasn’t anything else she could do, she went into the orchard and got them a bag of apples or went in the garden and got them some tomatoes or she got a bag of potatoes. I know one time (I will never forget that) she had a lot of potatoes. One of my brothers, Cardell, he was there. And she thought he did not have enough, I guess, so she made arrangements for him to take 3 or 4 bushels of potatoes home with him, you know. He said, “I don’t know what to do, I cannot tell her I don’t want them. I don’t have any use for them, unless I can find someone I can give them to.” And he had me load them in his car, and I never did ask him what he did with those potatoes. But he probably just threw them out, I imagine. At that time people didn’t really like to peel potatoes, they would rather eat something already prepared.

But they were just nice people. Good to everybody. And like I said, they had very little, by material standards, but they had everything else. They had respect and regard of all the people in the community. It meant a lot more than the money did. People didn’t look to them for the money, they looked to them for who they were.

Mike: That is the kind of legacy you want.

Hollie: Yeah!

Mike: Did you live in that house down there? [The log home]

Holly: Yeah. I wasn’t raised in that house, though. I was raised up this hollow about a half a mile from here, back on top of that hill between Taylor and Robinson. I was born there, and then when I was three years old we moved over...just before you come to this ole Mount Ovis Church that sits right on top of the hill. That house was right along the road. We lived several different places around here in the community, but none of them more than 10 miles apart. Because the way we lived then, if you went from one place to another to live, you couldn’t go very far because you were moving in a wagon or a sled, you know. I was three years old, but I can remember that day. You wouldn’t think I would. But I can remember when we started to move, they had a great big pile of wood all split up ready for the kitchen stove, you know. They burned wood in the stove, of course most people did, coal or wood you know. They burned wood, and I remember my dad saying, “Now that is one thing we are not going to be able to move. That’s just dead weight by the move, not useful.” In other words, it was the one thing that could be replaced on the other end. And it worried me more than anything else, because my mom was pretty bad to get out to get a load of wood. I thought he was just taking her away from worry, you know. That really made me feel bad as a 3-year-old. But once we got over there, things were really different. See, it was kind of like moving from Clay County maybe to Charleston or from Charleston out to Detroit, or New York. We moved over there, and we were getting used to nobody coming by, unless it was just a hunter or something, you know, back there. Over there, people were coming by in automobiles.

Mike: You talking about this place?

Hollie: Yes, that place where it comes to the church on the hill. And it was just like it was moving into wide open country. Because people come by on cars, wagons, team of horses, and people walking by, and kids walking by to school, and all that thing you know.

Mike: Real civilization!

Hollie: Real civilization! And it was altogether different from what we had been accustomed.

Hollie didn’t know much about their ancestors

While Hollie didn’t know very much about the Workman genealogy, I have uncovered a wealth of information; as an example, see the bowtie chart below.

-

Mike: Did either one of your parents ever tell you about their ancestors?

Holly: Not that much. That is what I say, I had all the opportunity back then to ask them those questions, now I wish I had. I really didn’t know anything, hardly anything about them. I know more now than I did while they were still living, because I just thought I would always be able to ask them anything I wanted to know. I remember them talking about people, but I had no idea who they were. I didn’t bother asking them because I was not that interested in it. Now I would ask them a bushel of questions. And even Ida, she had seen a lot…she was 26 years older than I was. And she had seen a lot, see she lived here a whole century. She was born in 1899 and died in 2002. She went through one whole century, plus a couple of years.

Hollie describes his mother’s and father's educations

-

Holly: I have no idea where she went to school. I knew she had gone to school to the 3rd grade, but I have no idea where she went. I have been asking all the family, and none of them knows. I think she told me one time that old Ramsey school where you come the hill up there where somebody lives there now in a trailer, I think. And almost all my family went to school there at one time or another, all the brothers and sisters went to school there at some time in their life, even Ida. She was 102 when she died, and she went to school there. But none of them could remember if the school would have been there when Mom was going to school. That would have been well over twenty-five years ago, you know. But it runs in my mind that Mom told me one time that that school used be down here at Eakle, on the creek, and it was called Buffalo School. I know she told me, that on the front of it, if you had the siding off it (that they put on it after they moved it up there) that it would have said Buffalo across it. I always wanted to take that siding off, but they tore that thing down, and I wasn’t around when they tore it down. So, I don’t know what it was. But she told me it said Buffalo right across the front of it. Nobody else seems to know anything about that. I’d like to know more about that, and I wondered if that wasn’t where she went to school. She lived at that place where Marmel lives now. She lived there all her life, until she married Dad. She never was away from there.

My mother was smart, too, I mean, for the third grade. When they went to school back then, they got an education for each grade. They didn’t just go through it, they learned. They had to know it. We used to get her to spell words for us, because they spelled them and pronounced the syllables in them as they went, you know. I couldn’t do it at all, you know. I could spell the word, but I couldn’t get that syllable and then spell the rest of the word, and then pronounce two syllables and go on to the next word and pronounce two syllables. She would pronounce each one of them, you know, just kind of a ritual type thing. We would get her to do that a lot. Now she could mathematically figure almost any kind of a problem in her head. But she didn’t know how to put it down on paper. She didn’t know how to write it down, but she knew how to figure it out in her head and give you an answer. She was good at it. Now my dad was really good at mathematics. He had it. He could put it down on paper, you know. He went all the way through 8th grade, and that was a pretty good education then. In a matter of fact, he could have gotten one of those certificates for high school at that time. There was one boy I knew after I went to work at the farm store, who got his teaching certificate from an 8th grade education. They had to go to school afterwards, you know, but they could start teaching. I can remember when they taught with a high school education, and then they had to attend school during the summer. They could teach nine months and go to school in the summer until they got some kind of a degree, you know. Then they could slow down a little.

Hollie describes Juditha’s lineage; Ramsey Cemetery; where his siblings are buried

-

Mike: Now, Juditha was a Hamrick.?

Hollie: She was a Hamrick. My Grandma and Grandpa…of course, he was a Hamrick, and my grandma was a Ramsey. And that Ramsey cemetery up there…he was the one that gave that cemetery. It was supposed to be family cemetery, you know. But it wasn’t long before the community was buried in it, and, of course, none of our family would have said anything. There are people buried in there from all over the county. The last time I was up there, there were infant babies buried in there. They couldn’t get a cemetery somewhere else, so they just brought them up there. There is a lot of Workmans buried in there. Yeah! But there are some of them not very well identified, too. But there are more other people than Workmans. I’ve got two sisters buried there and no brothers. My brothers were buried in different places. Like Walter, all the way up to Ansted. Donald is buried way up in Sutton, a little cemetery above Sutton. Edna is buried on Camel’s Creek. Oba, cannot think of the hollow, somewhere near Summersville. Eugene is buried at Sunset Memorial down below Montgomery. That is all of them, isn’t it? Oh, I haven’t been buried yet.

Nathan Melvrie’s Occupations

-

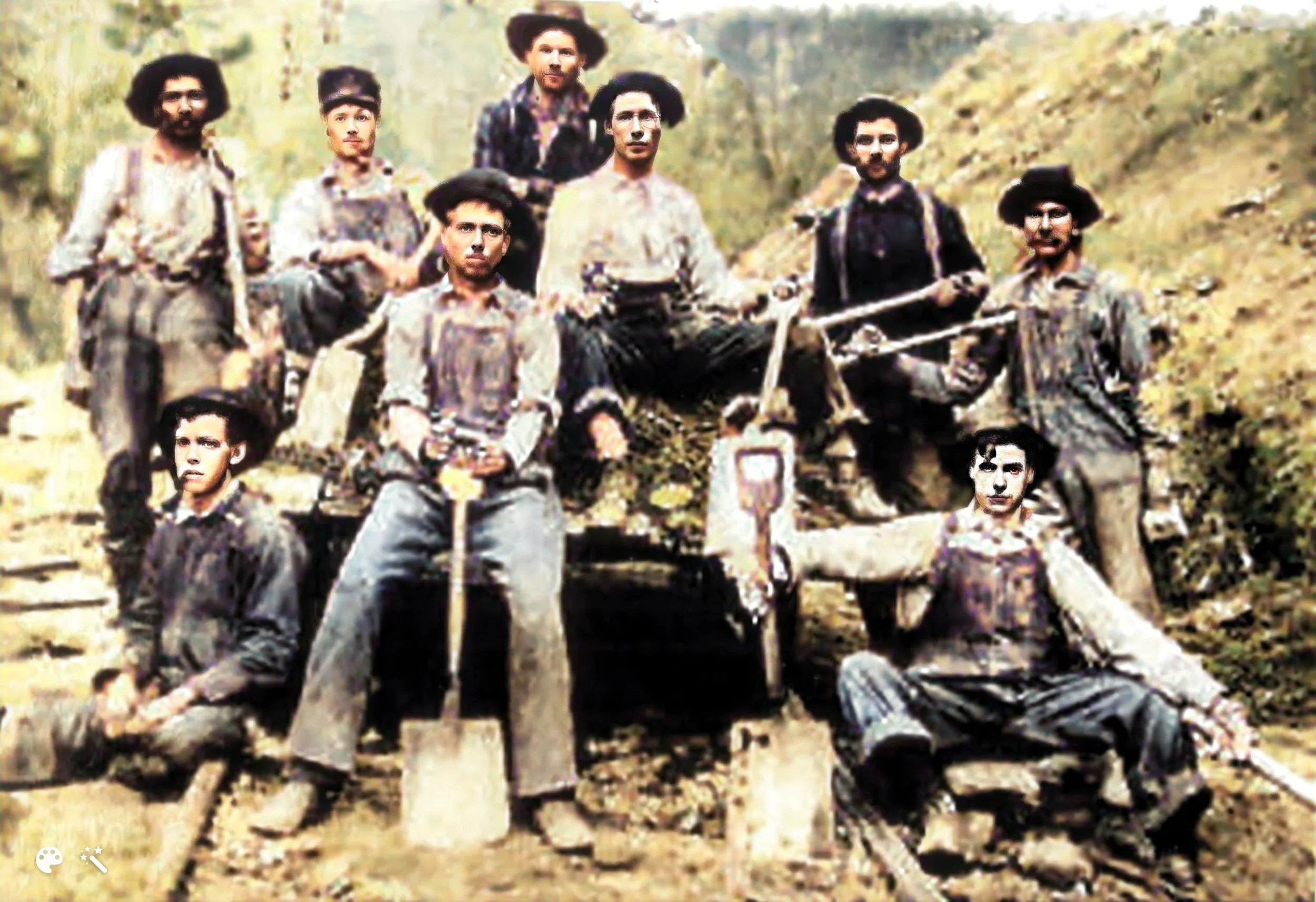

Mike: So, what did your dad do?

Hollie: Well, Melvrie was basically a farmer, but he did a lot of things. He did a lot of timber jobs. He made things like crosscut ties and cutting timber. When he was first married, he worked on this railroad down here. But he did not like that for some reason or another. He quit.

I remember one time he told me a tale about an old fella that worked down there, an old man called Hewey Fitzwater. He lived in the community until he died. He said they were working on the railroad down there, and they stopped for their lunch one day. And he had a tomato in his bucket and not many people ate sugar on a raw tomato. And my dad did, he put sugar on it instead of salt on it. He said he took that tomato out and sliced it and little thing…I don’t know what he had his sugar in, but he took it out and he just covered the top of it. And that old man he said “Melvrie, I don’t understand how in the world you could eat that much salt on a tomato.” He said, “The more you put on it, the better it tastes.” The next day that old man come down to work and he said, “That’s not true, Melvrie. I tried that when I went home, and I couldn’t eat it.” He hadn’t told him the truth about it. He didn’t know, but what he put salt on it. I don’t know if he ever did tell him or not. It was kind of funny. He generally went to bed early. He was one of those fellows that went to bed with the chickens and got with them or got up before they did. But if you got him started, he could tell some of the funniest stories…you know, really interesting. And he would just sit and laugh.

Nathan Melvrie’s Storytelling

-

Holly: He told stories of what happened to people, you know. A lot of them was things like being out before the place was settled around here. There would be bears and panthers and all that. He said he was riding a horse through just a trail, I forget where he said it was at, but it was in this general area. I think it coming from Muddlety through the woods there…and he said he was riding along and all of a sudden that horse bolted with him. And he said when it bolted, it threw him backward, and he caught the glimpse of a panther. It hit that horse and jumped, I guess it jumped with him…just barely missed him, because the horse was a moving on. But he said he almost lost him. As kids that was really…we just sat there scared to death, you know. The stories were really interesting to us, of course—we had to make up our own entertainment. Some like to tell tales. That used to be a real art.

No electricity, but a gasoline powered washing machine

-

Mike: You wouldn’t have had electricity?

Holly: Oh, No. We didn’t have electricity until we moved up where Marmel lives now. I started to say, yes, we did, but we didn’t. We had a washing machine that worked by gasoline, and I thought yeah, we had electric, but we didn’t. And another thing, after we moved up there, we converted that gasoline washing machine to electric. I guess she probably used that thing another thirty years, I have no idea. An old Maytag. It just lasted and lasted forever.

Mike: I don’t know if I have ever seen a gasoline washing machine.

Holly: I doubt very seriously. Right at that time wasn’t probably ten years after that. I guess they actually are still available, to tell you the truth about it. But they are hard to find. You can buy one of those things, but it would be really hard. That was very common then, you know, because 90 percent of the people in this area didn’t have electricity. They had it in Clay, but not in Dog Run. Actually, they had a little bit in Widen, because they manufactured their own.

Hollie’s Schooling

Picture of Clay HS

-

Mike: Where did you go to school?

Holly: I went to school…in grade school went up here to a school up here on Robinson. When we lived on Robinson, I went to the Ramsey school. I didn’t finish high school. I started at Clay, but we moved into Lockwood, and then I went to Summersville for a year. Then I moved back over here, so I didn’t try…could have gone to Widen, but I didn’t. Walter and Bertha tried to get me to come stay with them…and of course, my dad really didn’t want me to because they really needed us around.

Mike: Now, when you went to Clay, was my dad there at that time or was he…?

Holly: No. Oh yeah, he was there. No…yeah, yeah, he would have been there. After Mary Belle and I was married, we went to Morris Harvey, in Charleston. We went down there for a while. We didn’t go very far; the biggest part of my education I got it on my own. I learned by myself, after I came back from army. Mary Belle, she didn’t graduate either. She went to Clay High, but she didn’t graduate. We both got started late was the reason…we just kind of felt out of place, you know. But anyway, when I came back from the army, we decided to get our GED type diploma. We had to go to Glenville then to get it. She and I and Earl and Irma McKinney went up there one day. They wanted you to spend three days to take the thing, you know. We went up and they give you three hours the first day. I went through the whole thing in an hour and a half. I quit and walked out, and the instructor there said, “Oh, don’t give up so easy. Go ahead and fill out your time. A lot of people have to come back the third day to do it.” I said, “I’m done.” He said, “Oh, no, you’re not done now.” I said, “Oh, yes, I am.” He said, “Where is your paper?” I said, “It is laying on the desk.” He said to get it for him, and I went and got it. And he run through that thing…he said I have never seen that high a score of anybody in an hour and a half. He said, “I cannot believe it. I just thought you had just given up and quit.” Mary Belle finished in the three hours, herself. And Earl and Erma had to go back the next time, but they went back and finished theirs, too. He said, “I don’t know of anybody before that finished it in an hour and a half.” We didn’t study for it then; now they put you through a curriculum of some kind before you take the test. We just went with no instructions whatsoever, as to what there was even going to happen. We didn’t have any idea…

Mike: Well, that shows how smart you are.

Holly: But it just came naturally. It was easy to do, to me. I thought at the time, though, that if the rest of high school had been that easy, I could have done it. But you know, I never took a book home with me in my life. Never did have a book home with me, to study during the time I was in school. All kids were saying where’s your book at?” I could answer truthfully that I didn’t have any. I might use the school’s book if they loaned them to me. But they took them home, I just didn’t need to. I didn’t have any use for them. Most things like that, I never had any trouble really picking it up. I had a chance with a GI bill, of course, after I got that GED. I could have gone to college, but family was coming up next for us. I was almost twenty-one years old, and I just thought four years from now. And then, a college degree didn’t mean as much as it does now. I was expecting to work around here either on the railroad or coal mine. A grade school education was all you needed, so the rest of it was just wasted.

Hollie worked on the farm and for other people

-

Mike: When you were growing up, did you have a job, or did you work on the farm?

Holly: I worked on the farm. There was enough other people around; we hoed corn for people. Whatever was going on if they needed some fences built or whatever. But our work wasn’t like kids are today, if they would work today, most of them wouldn’t. But we went and instead of paying us, they paid my dad. It went to the family whatever was to be bought. He took it and decided, no matter if I worked, I didn’t get it necessarily. If somebody else needed a pair of shoes, it went to them. Or if they worked and I needed it, it was the same way. It was a family thing, the whole thing. On the farm, we would pick a calf or a pig or something and raise it and call it our own, but when it was sold it went into the family coffer. It didn’t go to us. You know most kids get it all anymore, you know, and they still won’t do it. Now we were glad to do it…to give it into the family pot. Never thought anything about it, really. We never said anything.

Mike: Never probably realized how poor you were, did you?

Holly: No. And I mean we had plenty to eat. Never went hungry. We wore patch upon patch, but we always had clothes, enough to cover us up. Never really bothered us, as a matter of fact, we were poor, but so was the rest of the neighborhood. So, it didn’t make that much difference. Now maybe some people that had steady jobs, well-to-do compared to us in a way. But still they just lived like we did. They still had a garden and still maybe had a cow. It wasn’t that much different between the ones that had money, except maybe they had little extra money. Here we didn’t have it.

The story about courtship rituals is told in more detail in the folder Nathan Melvrie Workman & Juditha Totten Hamrick, 1877-1965 (Hollie Workman Narratives).

Family recollections; courtship rituals

-

Mike: Do you remember anything else about your childhood or family, anything interesting?

Holly: No. I didn’t have a very interesting life. I didn’t lead a very interesting life.

Mike: Well, that is probably relative, but.

Holly: No, not really. I don’t know of anything particularly interesting.

Mike: Did your folks ever own a car?

Holly: No, never owned a car. That is another kind of funny thing. My Uncle Raymond, he bought a new Model T Ford. He lived over there just over the hill from where we lived. He bought him a new car (well that was before we lived up there, bought him a brand new one). He brought it up there, and he thought he’d learn to drive that thing. He would take it out in field to learn how to drive it. They told this on him anyway and I guess it was true, it was always told on him. He would take it out in the field and drive it around. He was coming up to a stump, and he forgot to get around the stump. He had driven straight for so long, he nearly forgot how to steer. And they said he was hollering, “Hey, Gee Haw, Gee Haw…and that thing wouldn’t go Gee, nor Haw...just run right up on that stump. He just got down and said, “Ah, shaw, I don’t want nothing like that.” They said he never did drive it again. Some of the family took it away. It is sort of like your great grandpa, Albert—he never drove a car, but he always had one. He always had someone to drive him.

Mike: That’s right, that’s right.

Holly: He would take somebody right off his job to take him to town.

Mike: Did you grow up with Dad? Or did you just see him occasionally?

Holly: Just seen him occasionally, cause Walter was married and gone before I was born. Because I can remember when I was three years old, he wasn’t there, anyway. Maysel was the last…not the last oldest, but the last one home when I was born. She was just there a little bit. I can remember her and Roy and their little courtship…didn’t amount to much back in those days. We lived up on the hill there, and he came up on the hill one night. At three years old you won’t think I’d pay attention, but I remember that vividly. He came up there, and my dad had a gnat smoke built out in the yard, about like that from the door where you went in the house. And Roy came up there. Dad had a couple of chairs out there hoping someone would come along awhile, you know. He came along and just went over and set down there in that chair. His courtship for that night was sitting right there talking to my dad, until he got ready to go to bed. And when my dad got ready to go to bed, that ended the courtship. He didn’t allow the girls to be outside or even in the house with a boy after he went to bed. So, he had to leave, and I remember he barely did get to say good night to her.

Roy Litton and Maysel: Refer to the folder Nathan Melvrie Workman & Juditha Totten Hamrick, 1877-1965 (Hollie Workman Narratives) for additional information.

Mike: Now, who was that?

Holly: Roy Litton, married my sister Maysel. And even as little as I was, I remember the other brothers and sisters kidding Maysel about Roy coming to court Dad, you know. That was the only one who saw him; Dad was the only one he talked to. But sometimes they would let them come inside and sit side by side in a chair. But they had to stay in the house. They didn’t go up on Poplar Hill or out along the ridge. They didn’t walk out…or get in the car and go off somewhere.

Mike: These weren’t arranged marriages?

Holly: Oh, no, they made their own choices. But they were expected to live up to whatever they were going to do. If they made the mistake, they were expected to rectify them…not to wait for somebody else to.

Roy Litton

Maysel Workman Litton

Eakle, WV Maps

More about the Workman Family Reunion:

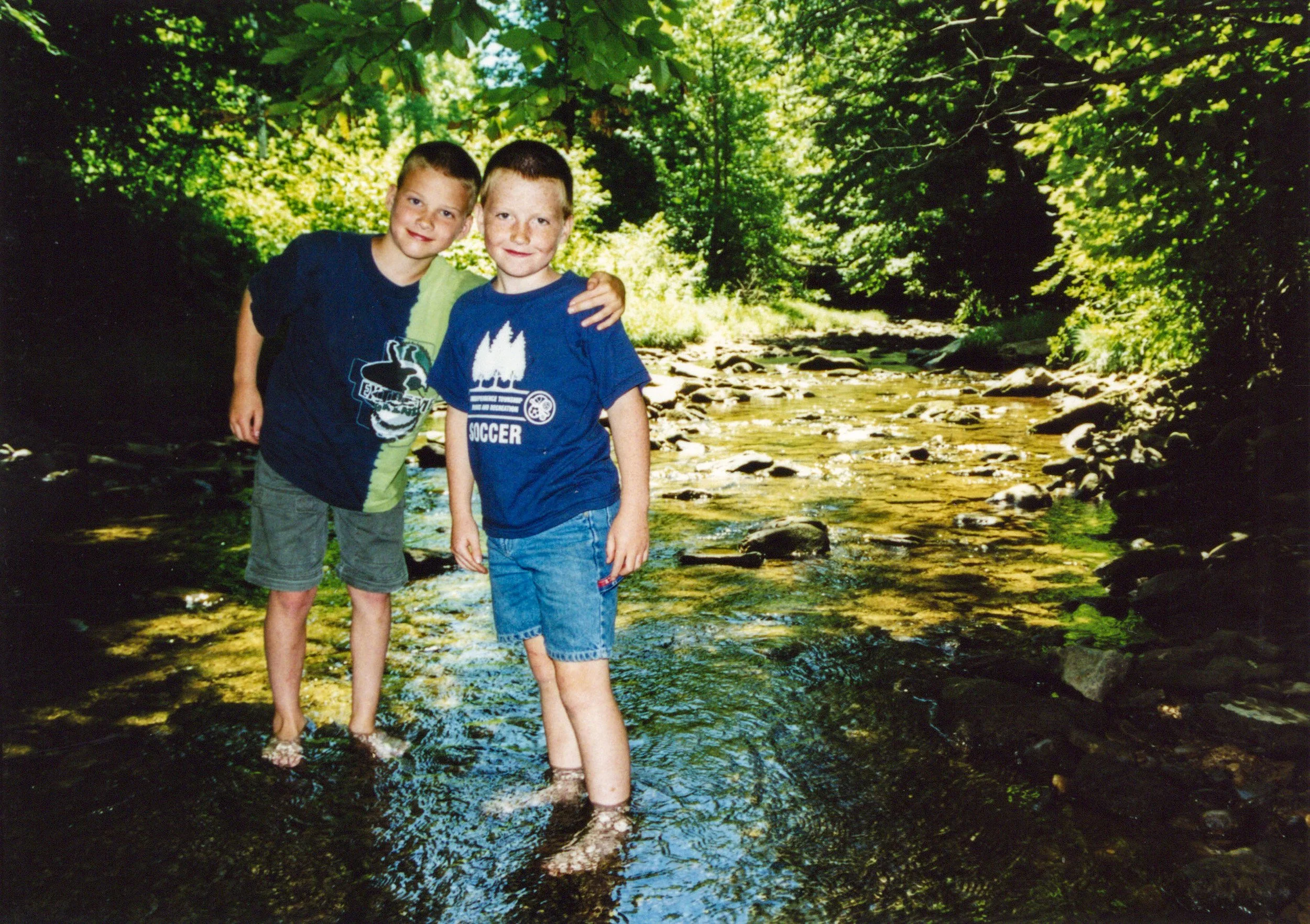

This yearly reunion, while open to all, was organized by descendants of Eugene Workman and held on Robinson Fork, where several of them have camps. I attended the reunions in 2001 and 2003. Holly was at both of them. The photos below are from the 2001 event, but the interviews took place in 2003. It was there that I learned of Holly’s autobiography and later obtained a copy. [I am still searching for my photos from the 2003 reunion.]

I am not sure if this event is still being held each year.

Workman Family Reunion Photos, July 3, 2001

The photos below are presented in a simple slideshow format. Click on the arrows to scroll forward or backwards. Most of them have captions which identify the subject matter.