Walter Edward Workman & Bertha Etta Mullins, 1931-1937 (The Roughs of Buffalo Creek)

A Note About This Folder:

In general, I have an abundance of family photos from each phase of Granny and Grandpa’s life…except for their time at Buffalo Creek. Probably for multiple reasons, they just didn’t take any photographs. Perhaps it was because of economic distress caused by the Great Depression, or the extreme isolation of the farm, or maybe they did not have a camera or access to processing. The photos that are posted here were either taken in later years or acquired from available resources.

What we don’t have in terms of pictures, we make up for with vivid storytelling from Uncle Damon and Uncle Doyle. Fortunately, I was able to make some high quality audio recordings so we can enjoy the memories. In most cases, I have included transcriptions along with the audio track. It would be my enthusiastic recommendation that you always listen to the story first. The word-pictures are terrific, and the passion and intensity are conspicuous!

One additional comment about the title. There is some uncertainty about the year they moved to the farm…whether it was 1930 or 1931. Dale was born in 1930, according to sources, in Adair. However, Damon seems to think that they moved there after Dale was born. For now, I am leaving the date as 1931.

The timeline below provides a summary of Walter and Bertha’s experience on Buffalo Creek. It was a short period, but one that was sprinkled with life-changing events.

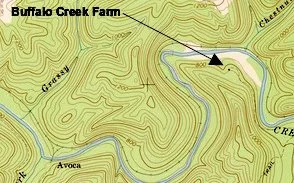

Buffalo Creek Farm

Moving from Maysel to Buffalo Creek farm

As mentioned in the previous section, the Great Depression caused their hardware business to fail. That’s when Walter and Bertha moved to the farm on Buffalo Creek. Damon said that the Albert Mullins family was from the Maysel area, northwest of Clay. It appears that the logging business led to the Mullins family acquiring a lot of land (including the farm on Buffalo Creek). Damon expands on this thought with the following narrative:

Mike: How'd they ever find that place? [Buffalo Creek]

Damon: Grandpa… way back in his times, it was in the Mullins family. The Mullins owned some property up in there and on up to the dairy farm, the Mullins used to own that. [The dairy farm was built and operated by ERC&L Company, in Cressmont. See the Resources section for more info.]

But this ole farm there that Daddy and Mom lived on was back in the Mullins family, back in the turn of century around 1900. Mom said she could remember standing there and watching when they started that railroad, when they come up the Buffalo surveying to build that railroad. That was in 1904, I believe. See, she'd have been six years old, I believe. And they [the Mullins] lived up there at that time. Grandpa just moved wherever he could get a few days’ work, just like everybody else did. You didn't have steady employment anywhere.

[To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below.]

[DEWv1: Albert gave Buffalo Creek farm to Walter & Bertha (10:46-11:32)]

And then when they did that... of course, my thoughts are that Grandpa [Albert] didn't want to put up with them, so he just moved them up on that old farm. Now whether Grandpa gave them the farm or whether...I don't see how they could have bought it. They were just too poor to have bought it. I just kinda figured he just gave it to them to get rid of them. See, we moved up there when Dale was just a baby, and he was born in 1930. So, we must have moved up there by the spring, early spring of '31, I'd say probably.

A visit to the Buffalo Creek farm

In September, 1970, my family (Denvil, Kate, Bus, Jaynet and Mike) traveled over to Clay to explore Walter and Bertha’s homestead on Buffalo Creek. As you can see on the map above, the farm was (and still is) very isolated. There is a road from Dundon to Avoca, the last portion of which traversed through huge GOB piles. These GOB (garbage of bituminous) piles are the material left over from coal mining, some of which is nonflammable. The piles shown in the photos below were cleaned up around the turn of the century. From Avoca onward (upstream) the only road is the creek bed itself. Fortunately, Dad’s pickup was up to the task. It also helped that the water level was low.

The train equipment in the photos was stored just east of Dundon. Engine #14 was in operation into the early 1960’s. It should be noted that the state of West Virginia purchased the bulk of the BC&G equipment for the Cass Scenic Railroad.

We were able to drive up to the farm (the last photo in the gallery below shows the open pasture where crops were raised). I don’t remember if the house was still standing at that time. We were later informed that it had been burned down by vandals unknown. I do not have any photos of the house…I am hoping that one surfaces along the way. Damon used to build wooden models of the house—those may be the only remaining remnants that show what it looked like.

Another visit to the Buffalo Creek farm

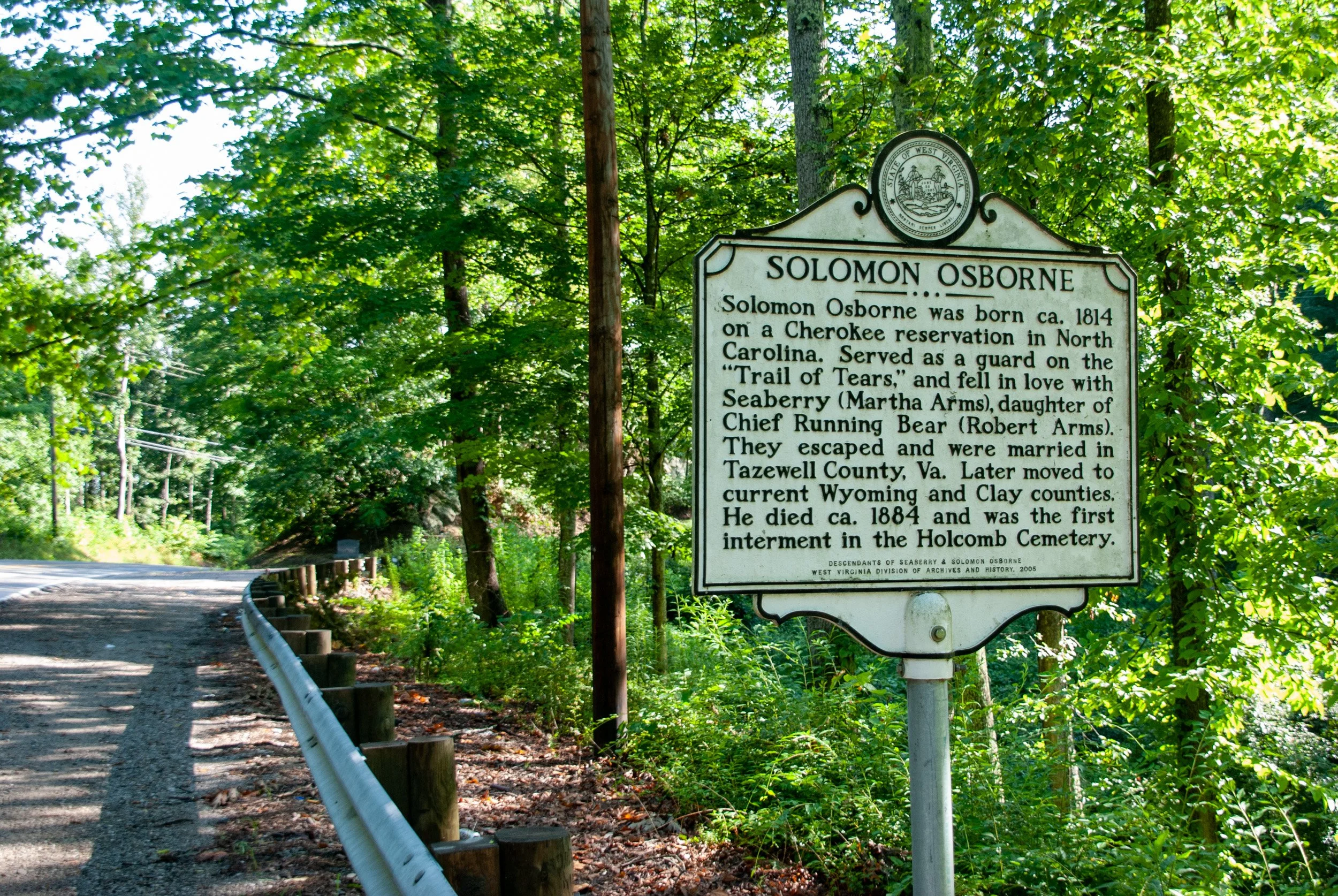

Forty-two years later, I made another trip to Buffalo Creek with Uncle Damon and Eddie. Clay is directly north of Fayetteville via SR16, but the road is anything but straight (or level). A little north of Bentree, there is an historical marker commemorating, Solomon Osborne and Seaberry Arms. These Cherokee Indians were my ancestors on Mom’s side…and also ancestors of Aunt Mae.

Eddie had enlisted the help of Jerry Nelson, who is the current owner of the Buffalo Creek farm property. I don’t know how much land he has now, but there was more than 100 acres when Walter & Bertha owned it. Jerry has a farm just off CR11, near Triplett. He uses the Buffalo Creek farm for hunting. Jerry guided us (over remote, 4-wheel drive only roads) to the property.

The photo gallery below chronicles the trip. Here a few comments about that day:

• The property is still remote and nearly inaccessible. You need a 4-wheel drive vehicle to get there.

• Jerry kept the fields cut down to attract deer. Deer is common in the area, as evidenced by the fact that we saw one as we were leaving the property. Trees on the rest of the property had grown unrestrained.

• The house that Walter and Bertha lived in was no longer standing. Apparently, vandals burned it to the ground. The foundation stones remained in piles on the site. I don’t know who originally built the house, but they demonstrated first-rate masonry skills. The stones had straight edges and flat surfaces, crafted only with hand tools.

• I noticed that the huge GOB pile at Avoca had been cleaned up. In general, the environmental impact of coal mining in the 1900’s has undergone significant remediation. I have read that trout are now stocked in the Buffalo Creek.

• In 2012, the BC&G railroad tracks were so overgrown that you could hardly see them. In recent years, locals have cleaned up (and repaired) the tracks and are making inroads with tourism attractions. (See the Resources Section/Clay County Info for details.)

Mae, Eddie and Damon, Fayetteville (2012/07/14)

Eddie and Damon, Fayetteville (2012/07/14)

Solomon Osborne Historical Marker, Rt 16, Clay County (2012/07/14)

Damon, Eddie and Jerry Nelson, Triplett, Clay County (2012/07/14)

Damon and Jerry Nelson, Triplett, Clay County (2012/07/14)

Eddie driving across Jerry Nelson farm (2012/07/14)

Jerry Nelson farm, 1 (2012/07/14)

Jerry Nelson farm, 2 (2012/07/14)

Jerry Nelson farm, 3 (2012/07/14)

Descent to Buffalo Creek along Chestnut Knob, 1 (2012/07/14)

Descent to Buffalo Creek along Chestnut Knob, 2 (2012/07/14)

BC&G Railroad track, overgrown 1 (2012/07/14)

Jerry Nelson talking to Eddie (2012/07/14)

Preparing to cross Buffalo Creek (2012/07/14)

Fording Buffalo Creek in Eddie's 4X Vehicle (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek, looking downstream (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek, looking upstream (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek farm, bottomland looking east (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek farm, site below where house stood (2012/07/14)

Damon and Eddie trekking to site of house (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 1 (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 2 (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 3, Eddie and Jerry Nelson (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 4, Nelson, Damon and Eddie (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 5, Eddie (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 6, cut foundation stone (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 7, cut foundation stone (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 8, cut foundation stones (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 9, cut foundation stones (2012/07/14)

Site of house, 10, cut foundation stones (2012/07/14)

Damon, site of hillside food cellar in background (2012/07/14)

Site of hillside food cellar (2012/07/14)

Damon (2012/07/14)

Eddie, Damon and Mike, site of house (2012/07/14)

This small ravine provided water sometimes (2012/07/14)

Overgrown site of house (2012/07/14)

Farm bottomland, looking west (2012/07/14)

Farm bottomland, looking southeast (2012/07/14)

Farm bottomland, panorama (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek, going upstream from farm, 1 (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek, going upstream from farm, 2 (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek, going upstream from farm, 3 (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek, going upstream from farm, 4 (2012/07/14)

Damon, downstream behind him (2012/07/14)

Damon, Buffalo Creek (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek, looking downstream (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek, Eddie, Damon and Nelson (2012/07/14)

Shallow section of Buffalo Creek (2012/07/14)

End of the "road", looking downstream, Eddie, Damon and Nelson (2012/07/14)

Return trip down Buffalo Creek to the farm (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek at the farm (2012/07/14)

Current owner of farm posted the land (2012/07/14)

Path away from farm (2012/07/14)

Deer are common in this area (2012/07/14)

Gated access. We went a different way (2012/07/14)

On the overgrown railroad track, headed toward Avoca, 1 (2012/07/14)

On the overgrown railroad track, headed toward Avoca, 2 (2012/07/14)

On the overgrown railroad track, headed toward Avoca, 3 (2012/07/14)

Avoca, site of former GOB piles (2012/07/14)

Bridge across Buffalo Creek at Avoca, 1 (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek below the bridge at Avoca, 2 (2012/07/14)

Buffalo Creek below the bridge at Avoca, 3 (2012/07/14)

Bridge over Buffalo Creek at Avoca, 5 (2012/07/14)

Log home, once the residence of Nathan & Juditha Workman, at Robinson (2012/07/14)

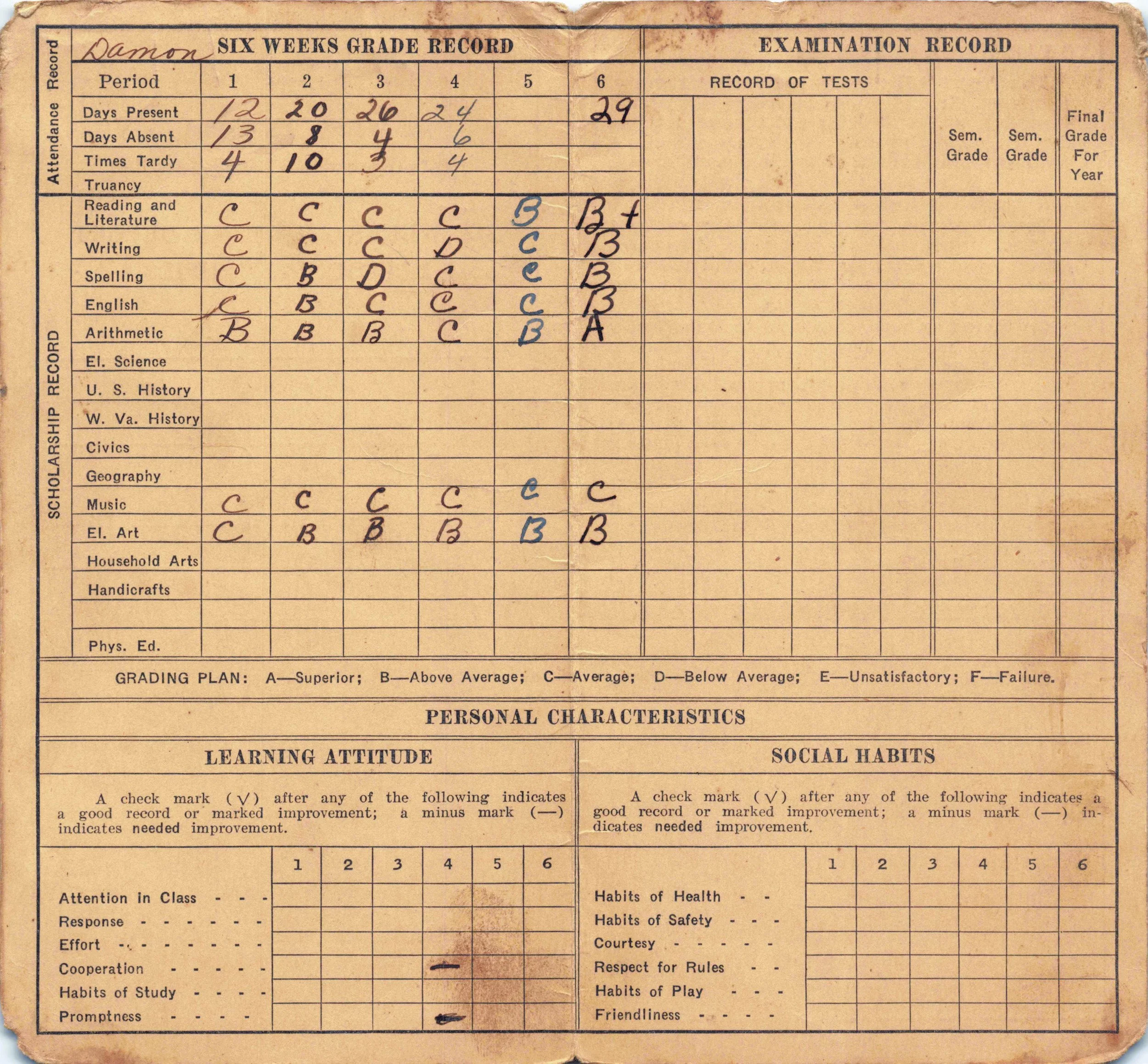

The School at Adair

During their sojourn on Buffalo Creek, the kids would have attended elementary school at Adair (see map). All of the details that I have are contained in the following audio clip that I recorded with Uncle Damon. To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: …up there on Buffalo, back in the days they built that railroad there, they just cut out barely enough room for to build a railroad. And we walked to school up there. There was a little community with a one room school.

Mike: Where was the school?

Damon: Up at Adair. That's an old community, Adair was. Mom's got people buried at Adair, that goes way back.

Mike: I don't know where Adair is, all right.

Damon: Okay. To go to it really, you'd go over to Clay, and go out that Triplet Ridge Road a couple or three miles. Turn to the right. Go down and you come down off the hill onto the creek on to Buffalo. You'd be at Adair, then you'd come on down Buffalo about another three quarters of a mile toward that old farm we had bought, see. Then from that farm on down to Clay was about four miles. But then of course we walked up to Adair to school. And there's a little railroad section there at Adair. All the way up the railroad, there were sections...ever so many miles they'd have...you know what a railroad section is. About four or five houses and about 4 or 5 men and their families lived in ‘em. They was the ones who kept the railroad up in that section. Of course, their kids went to school there and what scattered few people was there. Had a little one room school there. Me and Eddie went back in there, one time later, after Eddie was grown and worked for Pittston Coal Company. He was land agent there for Pittston Coal Company. We went back up there. There wasn't a stick of nothing there—maybe a gate post and that was about all. but we did go in that cemetery and some pretty nice stones.

Mike: Are they marked?

Damon: Oh, yeah. A lot of them are—of course, a lot of them are not. I talked to Carl Wilson here some time ago and he said they still was still running it. Old timers wanted to be put to rest back in there where their people were.

Mike: Was Adair on the map?

Damon: I doubt it. I've got a Clay County map [probably meant a USGS topo map] in there and can show you that old house. It's on that map. Right on that Clay County map. Go out Triplet Ridge, to Chestnut Knob and we lived right across the creek from Chestnut Knob. I remember that well. It's on that map. I'll look at it in a little bit and see if Adair is on it.

Phyllis catches up with Denvil

Denvil and Phyllis graduated from high school in the same year, although Denvil was 20 months older. Somewhere along the way, Phyllis moved ahead a grade. My guess is that this occurred early on. Since their elementary schools were small and short on teachers, combining grades would have been a way to maximize teaching time.

Five attend Adair School

Five of the kids attended the one-room Adair School: Denvil and Phyllis for 5 years; Freda for 6 years, Damon for 3 years; and Dale only one. [These are calculated numbers, based on their age.

Damon’s 2nd grade report card is the only record that I have found. It is interesting that Lenna Mullins (a great-aunt) was the 3rd grade teacher. The principal was Ezelle Ramsey (perhaps another cousin?).

Riding the train

Denvil and Phyllis would have ridden the train to high school for their freshman and sophomore years (1936 and 1937). It is about 4 miles to Clay (each way). They would either wade across the Buffalo Creek (barefoot, of course) or walk about 1-1/2 miles down to Avoca where there was a bridge. Dad told me that he would often walk the entire distance.

Life on Buffalo Creek

Life was hard on the Buffalo Creek farm. It was isolated; they had no close neighbors. There were no roads to the house. The BC&G Railroad was their only connection to civilization (and the nearest bridge across the Buffalo Creek to the railroad was a mile and a half away).

There was no electricity or natural gas for cooking or heating. A wood-burning fireplace provided heat, although they may have had a coal-burning furnace later. Coal was certainly abundant.

Their sojourn on the farm came in the middle of the Great Depression. Everyone was affected.

Raising and preserving food was nearly a fulltime job. Damon said that Walter was not a farmer. At the very least he was an inexperienced farmer. He supplemented his income by making coffins. I am not aware of any other jobs he may have had at that time.

The kids matured early in life; they took on adult responsibilities while still children.

We can look at the farm today and tend to romanticize it, forgetting how difficult it would have been to live there without modern conveniences.

The following audio recordings (and transcriptions) give a firsthand account of what life was like for the family. As you listen to Damon and Doyle tell the stories, imagine yourself in their shoes.

After reviewing these recordings multiple times, I have to say that I certainly admire the character, perseverance, and courage demonstrated by Walter and Bertha, Denvil and Damon. As you listen to the stories, I hope they inspire you as they did me.

Damon and Mae

Damon, Dale, Doyle

Buffalo Creek Recollections—circa 1932

Doyle was born at home on the Buffalo Creek farm (in 1932). So. he was only five when they moved to Bentree; consequently, he had very few actual memories of his time there. His recollections were based on information passed down from various family members. As with Damon, Doyle emphasized the remoteness of the home and the hardships of living off the land.

The USGS topo map clearly shows the location of the house relative to Buffalo Creek. The map shown here was published in 1967. I have seen an earlier version issued in 1904 that shows the same thing. This tells me the house was built before 1904. I do not know who the actual builder was.

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Dianne: When you moved from Buffalo Creek to Bentree, do you remember that?

Doyle: I was born up on Buffalo in 1932, and Mom and Daddy moved to Bentree on April Fool’s Day in 1937.

Barbara: I was born in Widen in 1933, and we moved from Widen to Glen in 1937.

Doyle: So, actually, we moved to Bentree, when I lacked about a month of me being about 5 years old.

Mike: Do you remember that at all?

Doyle: A little bit. I remember a little bit about being on the farm up there in Buffalo Creek--not very much of anything. But I remember when we moved to Bentree--I can remember things. Now you are talking about Buffalo. It was Dolly Parton, no it was Loretta Lynn that was raised in the country, or something. Well, when we was born up in Buffalo, we was born in the country. You couldn’t even get an automobile within a “hoot and a holler” of a house. [Hoot, as in the call of an owl. Holler, as in a loud cry or shout.]

Mike: I have been over there a couple of times.

Doyle: Well, I think you might be able to get a truck in there now, or something. But when Mom and Daddy lived up there, Daddy had to park the car way up on top of the hill across from the house and walk down the hill. And if Buffalo Creek wasn’t too high, you could pull off your shoes and wade the Buffalo Creek to the other side. If it was high, you had to walk up the railroad track about a mile or mile-and-a-half and cross the swinging bridge and then come back. There was no roads in there. Period. And when they moved from there (I don’t know how they moved in there), but when they moved [out], they hauled their stuff on a horse and sled around there and carried it across the swinging bridge and loaded it into a railroad car and brought it down to Dundon. Then they loaded it onto a truck, on over to Bentree. But I never did find out much about that place. I asked Damon about it one day. See Grandpa Mullins owned that old place. And I never did find out where he got it or very much about it. But he got it and give’d it to Mom. You see, that was during the depression. Of course, Daddy did not have much of a job, but he worked on the sawmill, and stuff, some, and they moved up there. And of course, Mom and them farmed, and Denvil and them farmed, and it was rough days back in them days. And they stayed, well both me and Darryl was borned over there.

03:03

Mike: Were you born at home?

Doyle: Yes. And I am not even sure there was a doctor there. I was talking to a woman the other day, and it was in the Mullins family how come I talking to her. She is a Nelson. Herman Nelson’s wife, and she--this girl--Herman Nelson told me that her mother, her mother’s name was Chessie. She would have been a first cousin of Mom’s, I believe was right. Just a minute I am not sure if she was a first cousin or second cousin. She told me that her mother helped deliver one of two of us. Which she may have helped deliver me. And then mom helped when a couple of her kids was born. Now to tell you whether or not there was a doctor there, I don’t know. Apparently, there was some doctor signed my birth certificate. But I do not know if they had a doctor there or not, to tell you the truth. See many of the people in those days were born without a doctor. People just had midwives.

[Sidenote: Jerry Nelson, bought this property and is the current owner. Damon, Eddie, and I contacted him in 2012. He took us over to the farm on a 4-wheel type of road.]

Barbara: Was that called Avoca in there?

Doyle: No. Avoca’s on down the railroad track. [Toward Clay] We was up above Avoca.

Barbara: What was the in-between called then?

Doyle: Well, it was just called wilderness then, I reckon. It was…I don’t know if they called it Chestnut Knob in there or something. I got a map of it--well it is on the computer. Allen got me a set of topographical maps, and me and Damon can show you right where the house sat.

Barbara: Well, tell them about the women that come and the sauerkraut.

Doyle: Well, there was a woman…back in them days…. (These people, these days, don’t know what hard times is; they just think they do.) In ‘32 there was not Social Security, there was no welfare. Period. There was none. This Cora Bell Hamrick, Cora Bell Nichols…

[He and Barbara went back and forth--it may have been Keenen]

Anyway, her name was Cora Bell, and she had come down. She lived back up on top of the hill from Mom and them. And she came down there and would want…Mom and them would pickle beans. And I don’t know if you have ever eaten pickled beans, but I don’t like them.

Mike: I have had them.

Doyle: They are sour like, but back in them days you canned or pickled or whatever you done. Well, every few days, every once in a while, you put all these beans in that old churn, and you would weight it down with a rock or something. And every once in a while, you had to clean the brine off. And Cora Bell would come down and ask Mom if she wanted her to clean her pickled bean jar for a mess of pickled beans. She would do all that and get a quart of pickled beans to eat and go back home--and then you got something to eat. There were a lot of people that did not have very much to eat. And I can remember her coming down to do that.

Barbara: Did Phyllis and Freda ride the train?

Doyle: I don’t know whether Freda did or not, but Denvil and Phyllis--they walked from the house down across that swinging bridge and caught either the train or that Bradley car, that they called it. The old man Bradley had a rail [passenger] car, and they rode it down to Dundon, and they walked over to the high school. That is how they went back and forth to high school. I believe we moved from Buffalo maybe the year that Freda was in 8th grade. When we came to Bentree she started there at Clay [High School].

Mike: How many rooms were in that house? Do you remember?

Doyle: I don’t know if it were three or four. It was a two-story house. But before Daddy moved there, this old man Worth Davison lived there. I did not know, but Damon was telling me that he lived there and about all the windows was broke out of it. And the paper or something nailed over the windows and stuff, because they could not get the glass and stuff to put in there. So, most of the windows was nailed up, and when Grandpa give’d it to Mom and them, they had a time of getting Worth to move out because he did not have nowhere to go. And when they moved in, the house was in pretty bad shape. And they got it and fixed it up, putting window glass in it and some stuff and they lived there about 6 years, I reckon.

Hardships on the Buffalo Creek; food storage problems—circa 1932

Perhaps the biggest problem they faced was raising and preserving enough food to last from year to year. The only refrigeration came via natural means. The photo shows the remains of their food cellar. According to Damon, it did an adequate job of slowing decay…but it was never meant for long-term storage. It’s a miracle they didn’t die of malnutrition.

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: Boy, that was a rough place to move into when we moved up there. And the windows, a lot of them were out of the house, and no barn, no outbuildings, and fence and all.... The people that lived there before just burnt up everything they was for firewood. There wasn't a thing around...

Mike: This is up what's called Sangamore?

Damon: No, that was up Buffalo, up from Dundon. When we moved there. I can just remember sketches of it--and by the time I got old enough to remember the details and stuff. I can remember when Doyle was born, and I'm about five years older than him--I guess pretty close to it. But you know how when you're young, you just remember the little details and stuff like that. And Mom and Daddy wasn't farmers. To be a farmer back in those day and times you had to know something more than just going out there and plantin' corn and potatoes. You had to know how to preserve them and how to put them up, and how to keep them after you got stuff raised...you didn't have no jars to can 'em in. That's what happened to a lot of people back then on a farm. They'd go out there and raise a crop, but when fall come, they didn't know what to do with it. If you didn't know how to take care of it, in little while you didn't have nothing to eat. The big skill in farming is taking care of what you raise...a whole like today is taken care of your money. Mom strung beans and put them up in the attic and dried them...didn't have jars to can 'em in. String them up on thread, hang them up in the attic, and they'd dry and we'd cook (we'd call them leather breeches) And they wasn't bad either. And she had two three churns that she would put to kraut, pickles, and stuff like that in. See, you didn't have the jars like people's got now. People's even quit canning now, you might say. Mae used to can using every jar she had; she'd can something in it. We didn't have the jars back then. Even if you had, you couldn't can, because the lids were no good. You had them ole lids with a rubber band on them, you know, and you'd work yourself to death and can something up, then it would spoil.

14:31

We had a neighbor there who showed us how to bury apples. Dig a big ditch and put leaves in there and put all the apples in, and then cover them up with leaves, and then cover them up with dirt. And one of the rules: you didn't open the apples ‘til Christmas. Then you start eatin’ at the bottom. Boy, they were good. And you buried your potatoes. You always buried them on the hill--dig a ditch up and down the hill. You didn't want to do dig where the water would stand in.

Mike: You'd bury them right in the dirt?

Damon: Oh, yeah, we would dig a ditch right up hill. Took the plow, don't mean you just take a mattock and shovel. Then us kids would take hoes and dig ‘em up and put leaves in there, put your potatoes all in there. Then cover it up with leaves then take your dirt and put it back over it all. Keep from freezing. It wouldn't grow; it was too cold. The ground would be too cold for it to grow. And you could leave those potatoes in there to all winter, if you had them buried right, Bury your cabbage and potatoes and apples. There's lots of stuff you could bury in the ground and preserve ‘til…. Made it real nice to go out there in February or March and get you a big bucket of potatoes and cook them. Or the apples or anything, some good eatin’ then. Of course, now in summer you didn't want for anything hardly. You had plenty of stuff to eat.

The same way with raising a hog or a beef or anything like that. A lot of people could raise a cow or raise a hog, but when they killed it, they couldn't do nothing with it, you see. If you killed the hog up in November, come two or three warm days your meat spoiled. With no refrigeration, there wasn't nothing to do with it. So, you waited till winter, ‘til the weather got really, really cold (usually after Christmas). Daddy had picked the coldest day in the year to kill a hog. And you killed the hog and cleaned it up and hung it. Hang it up by its back legs up on a scaffold, wash it down real good, and hopefully that night it would freeze just like a brick. Once that hog really froze good (and they claim that got all the body heat and everything out) that would save a lot better. If you killed a hog and let a warm day come, it'd spoil on you. You didn't have no jars to can it in, hardly.

Mike: Did you ever use salt to cure it?

Damon: Well, they could put salt on it, and they used to get a barrel, and make brine. Kept the flies away from it. That's what spoiled meat so bad. Flies would bite it or lay eggs in the meats and then start spoiling.

18:20

I don't how those people back years and years ago [survived]...because you know you see movies and stuff you know where they got big dinners. I don't know how they preserved all their food. Because you had no way of canning and putting it up. If you had a big cellar big enough was a way of preserving a lot of stuff. But to build a cellar properly.... We had an old cellar that it had been there (like I said every outbuilding had been burned down for firewood). and Mom's uncle came, Uncle Marshall and he helped us restore that old cellar--and put a door on it, build a roof over it. The rocks are still there in the hill and of course you know what a cellar back in the hill is. Then you could keep potatoes and apples and stuff in that cellar. But before we had that, we put them in the ground and kept them.

Denvil getting corn ground at Rhodes’ Grist Mill—circa 1932

Walter alludes to getting groceries at Rhodes Store (in Swandale). This was actually the ERC&L company store; Jay Rhodes was the manager. This photo was taken in the 1920’s.

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Mike: You told me a story one time about Dad [Denvil] when he went to get some grain...that was obviously before you moved.

Damon: Took the corn to the mill--yeah, we lived there on Buffalo. I can't put that year together, but we lived there...I'm guessing he would have been seven or eight, maybe nine or ten years old. I was about five years younger than him. I'm just guessing, I'd have been about five, four or five and he'd have to have been nine or ten. But you had to peel or shell the corn When you farmed your corn and brought it in you laid the very best years back for seed, then the next best for meal, then the next you fed your livestock. So, we had our corn, and it had to be real dry before grinding in the mill.

Mike: It was corn that you raised right there?

Damon: Yeah, oh yeah.

Mike: How much would you have had in a season?

Damon: Oh, how many acres or loads? I don't know. You'd raise all the corn you could raise. We always had the need for corn, see.

01:36

We'd bring that corn in and hang it up on the walls, the fireplace.

Mike: Right in the house?

Damon: Oh, yeah, get it dry. When that corn hung there for so many weeks or days, we decided it was ready. Well, you'd shell the corn. Some called it peeling, but you shelled the corn off the cob onto a sheet. And we'd all sit around that sheet and shell corn. Burnt the cobs. That's what you used for lights, to burn the cobs and sell the corn. Then when you got it all shelled, you put it in two sacks. Balanced it, see; put it in two sacks. Then at daylight the next morning, they put Denvil on the horse and the bags of corn across the horse.

Mike: No saddle on the horse?

Damon: I can't remember. I doubt if he had a saddle on at all. I don't think so. But he started to the mill. Gosh, the mill was...the meal would have been...I mean you're going five or six miles up to that mill.

Mike: Is it up the creek?

Damon: Yeah, you went up the creek and then up what was called Dog Run. A Fellow up there by the name of Rhodes had a grist mill where you ground corn.

Mike: That right on the creek?

Damon: It was right beside it. But I believe maybe he used a gasoline engine then. But a lot of these corn grinders had waterways.

03:19

But anyway, they ground corn for you, and then you had to wait your turn. If you got there at certain time and there's somebody ahead of you, you waited till it come your turn to get the corn ground. Then the man unloaded and took the corn off and measured it. Then he took his toll out of it, see. He took about a third of it, to grind it. So, when he got it ground and put it back in the sacks and put it back on the horse, Denvil started back home. It was probably well, well up in the afternoon by then.

Mike: So, he would have had two big burlap sacks....

Damon: And then when you started back, you just had two small bags of mill.

04:12

And we were really, really looking forward to having some bread, see. Wood--had excess wood cut for the wood burning stove you know, and all that waiting for him. And we waited, and waited, and waited, and then every little while you went to the living room to look out the window. You could only see a little ways out in the road then around the hill, see. And we waited until dark; he never come back, see. So, Mom, she really got upset, or Daddy got upset really. He went and got his own coat on, got the lantern, and put kerosene in it and started out. And he said I'll bet you when I find him that I'll teach him how to come home. So, he started out to look for him, and he got around to the end of the farm, and it was what we call the "big gate". That's where an ole big gate was.

05:14

There were nails and all that stuff in the fence post, you know. when he [Denvil] got to the big gate and got off and opened the gate and brought the horse through, a nail caught the sack of meal and tore a hole in it. So, he just put his hand over that. And he couldn't get the horse to go, with him beside of the horse. I guess it was afraid of stepping on him or something. And he kicked the horse and tried to get it to go and all that. The horse just kind of turned around and around with him, see, and he was trying to get it to head on out.

Mike: What time of day was this; it would have been night?

Damon: This would have been dark or by dark. He kept waiting for somebody to come to his rescue. Because if he turned that sack loose, all the corn (he couldn't get it off the horse), all the meal's goin' to run out. So, Daddy got his lantern lit, all this, and went to hunt for him. And he found him, and of course, he got the sack up off the horse and whatever else he did. He came back with the horse and the sack of meal. And I know it was snowing, and snow just looked like it was going crossways, you know. And we were all at the window watching. We seen the lantern coming back. We was all looking for them. We figured he really thrashed him good, see, for being gone so long. And he just told my mother to take him in the house and put his feet and hands in water ‘cause they might have been frozen. But they weren't. Of course, he'd been walking around and around that horse. But the horse wouldn't go on to the house with him...if he'd have gotten completely behind it or in front of it, it probably would have. But he couldn't get the horse to get go like that. Anyway, they got the meal unloaded and the sack in the house, baked the cornbread and all of that...they was whole lot to it but.... I can remember my dad had big old beards, real heavy, you remember. And he only shaved once a week or maybe not even that. Ya didn't have anything really to shave with, you know, hardly, back in those days. An ole straight razor. And there's big tears comin' out of his eyes and run down into the beard, you know. Boy, there's something bad wrong with my dad. I'd never seen him cry before. I thought there's something really, really happened to him. I guess he had really bad-mouthed Denvil for not coming back home and got out there and found that he was trying to preserve the meal, I guess. But anyway, we got the bread baked just like a real feast.

Mike: It probably wasn't snowing when he left in the morning?

Damon: Oh, no. No, it wasn't snowing that morning, but it was cold and began to snow.

Mike: So, that was like in November?

Damon: Oh, no. It'd been on up in, very likely, in January.

Harvesting corn, feeding livestock, raising crops; Walter not a farmer—circa 1932

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

See you cut corn, then you shucked it. Then you went through and shucked it. Took your corn out of shuck. And put it on a sled and brought it in, and that's where you graded it when you brought your corn into the barn. You always picked out the very best corn to have to plant the next spring. Then the next best for your meal and rest for the stock for your hogs. Gosh, you keep an ole horse there on the farm, you had to feed it 12 months a year--they'd eat up a lot of corn.

You couldn't deny it its keep through the winter you know because you had to keep the ole horse together, because the next spring he was gonna start plowing.

Mike: Did you have hay?

Damon: Yeah, some, and more oats. And the horses and cows eat a lot of the corn, what we called fodder. You know after you took the corn off this, we'd put that in and they'd chew around and eat it. We didn't have a lot of hay. Most of the hay they cut back in those days, they cut it with a mowin' scythe.

10:52

O’ course, some of them ole farmers could do pretty good with that. But my dad wasn't really a good farmer. But I've seen people that can take these old, big scythes and a field. Mae's dad could take one of them scythes and come around you know. And go back and come around again. When he went all the way to the end of that field, they'd just be a row of hay a layin’ there... or oats or whatever it was. Then cut another row, another row, another row. Then when you got that field cut, why you'd go through and rake it. Or if it was oats, of course, you’d tie it in bundles, usually and brought ‘em. And the hay, you just raked it up and stacked it up right in the field. You know, they'd lay down some fence rails or something there and just start putting that hay around stacking it up in stacks.

Walter made coffins for the locals—circa 1933

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: Wasn't very much in farming. You know, back in those days, the biggest thing ya lived off of was the farm.

Mike: You said he made coffins or something like that?

Damon: Oh, yeah, he built coffins...see back in those days, a lot of people, old people, they would have maybe a tree on their farm, or go and pick out their lumber for a coffin. And lay it up in the barn. A lot of those old timers…you'd go and look up in the barn and their coffin lumber would be up there, see. A lot of those old timers did that back then.

Mike: They'd have taken that to a sawmill to have it...?

Damon: Or go to the sawmill and get it; or take a log there and have it cut. Some people maybe would take a log and have it cut into their caskets, their coffins. And they'd have it all dried and ready, and everything, see. And then you got right up to the time when they died. Well, they'd bring that lumber to you, and you'd start shaving her down.

Mike: So, Grandpa made coffins?

Damon: Yeah. Mom would line 'em; put that ole blue stuff in it. I don't what it was...some kinda real cheap lining. You put it with tacks inside. Make it look real soft and nice. I can remember them making 'em. That porch was just high enough--just right for Daddy to stand and use that big ole hand plane, you know, planing the lumber. And he'd plane that lumber down, according, you know, ever how big the man was...how long to make it. And it was small at the bottom, you know, made just like you see coffins.

02:09

Damon: What did you say baby doll?

Mae: Tell them about the time that people stole the meat out of the house. [This story was told later.]

Damon: The ones that could afford it would put handles on 'em and hinges that of nature, you know. They'd open the lid up, you know (that was the fancy ones). But a lot of 'em didn't go that far. They'd just make it and lay the lid down beside of it, and when they got ready to put them in the ground, they just picked the lid up, put on there and nailed it on. And you're done. I mean that was, in other words, several dollars cheaper (or a few dollars wouldn't have to be several, but a little bit).

Uncle Washy Mullins’s funeral story—circa 1933

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: I know I went one time, and I can remember that bothered me forever so long. Kids back then didn't have as many things to think about as they do now, you know. When they buried Uncle Washy (that was Mom's uncle).

Mike: What was his last name?

Damon: Mullins. And he died and they laid him out (as they called it back then). Some of the people just come in, shaved him, or whatever they did, put his suit on him.

Mike: Now, they didn't embalm or anything?

Damon: Oh no. They just put them in the box.

Mike: And when they died you probably would have had the wake or viewing right then?

Damon: Yeah.

Mike: Right there the next day, right?

Damon: Well, within a couple days, when they got them ready. And they said all Uncle Washy had was his watch--he had a watch with a chain on it.

Mike: What was his real first name?

Damon: They call him Uncle Washy. I don't know...Washington, or what they called him.

04:09

He had about four boys, and looking back, there was about three of them that were illiterate. The oldest one I think he had worked, went away maybe, had worked a little bit or something like that. But they couldn't agree on who was going to get the watch. (That's what my dad told me later, and I was just a little kid.) But the yard, you set up here on the bank, and looked right down on the porch where the coffin was, see. And the preacher got ready to preach the little, short funeral. Daddy had the nails and the hammer. They put the lid on it. And this oldest boy came up and knelt down beside of his dad's casket. He took that watch out (he had a vest on you know and that chain went across that vest). He took that watch out, and set it, and wound it. Boy, you could hear a pin drop, there wasn't nobody sayin' a word--nobody never said a thing. And he wound that watch, and set it, and put it back in his pocket, pulled his coat back over it, and they nailed the lid on it. Took him to the graveyard and put him in it. And that bothered me for years after that. I wondered how long that watch run, why they put that watch in there why didn't they....

Mike: They couldn't agree, couldn't...

05:44

Damon: But I didn't know that, see. I just thought what a waste it was to bury that watch, because that poor ole guy wouldn't never know what time...why, he couldn't check it anyway, you know. They put that watch right in his pocket and sealed him up in that box, nailed the lid on it.

Mike: So, would Grandpa have made that coffin?

Damon: Um uh. [Yes] Now some of the coffins he made, they put handles on them. Some of them they didn't--they carried the box. Usually, they'd put it on a wagon or a sled or something. Take it right to the graveyard, ya know, and put it in the ground and bury it.

Mike: So, when did he make that? Was he in that business when you were on Buffalo or was that before?

Damon: No, that was while we was up on Buffalo. Mike, there's all kinds of pop to drink.

Mike: Yeah, I'll get some.

Damon: What kind do you want? What do you want Brenford?

Slaughtered hog stolen from house on Buffalo Creek, outside Damon’s bedroom—circa 1935

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Mae: Damon, tell all those stories.

Damon: I know what she is talking about now.

Mae: Damon, tell all them good things!

Damon: Oh, stop, that’s a bad story.

Mae: Tell all them good things, because those grandkids and great grandkids will get a big kick out of it.

Damon: You tell it!

Damon: Back on the farm when it got cold weather, it would come time to kill your hogs. You always had a meat house to put it in. You always waited to the very coldest part of the winter, kill your hog, and hang it up so that it would freeze. My dad went and got this man to come and help. Daddy wasn’t a very good farmer, when it came to cutting up and killing hogs. He came, and they killed this hog and hung it up and washed it down real good. It froze that night, you see. So, the next day they cut it up…what they call quartering it. Cut it in four quarters, cut the middle part and the backbone and the tenderloin and all this. And they worked on it a long time. They were getting it cut up like it is supposed to be. They salted it real good and put it on this table. Well, the room is built right on the edge of the porch, the back porch. And mine and Denvil’s bedroom was right again that wall.

Mike: Where was this, up on Buffalo?

Damon: Up on Buffalo. In other words, I was sleeping right against the wall, and on the other side of the wall this meat was stored on that table. The whole hog it would be…never eat a slice of it, see. The whole entire hog was there on it. So along in about the middle of the night, something woke me. I was about 5 or 6 years old. And when I woke up, I could hear them pulling that meat off the table. Big hams and shoulders and stuff and taking out of the door, of the meat house on the porch, see. They carried that entire hog away that night. The next morning when we got up, why I jumped up and went in the kitchen. Well, you see when you went out the kitchen, you went out on the back porch right close—went right in that meat house. I run in the kitchen, and Mom had her butcher knife and big old dish pan. She was going out there to cut some of that fresh meat for breakfast, see. And I asked her what she was going to do, and she said told me. And I told her, “There ain’t no meat out there. Somebody stole it all last night.” She told me I was dreaming, see. And they lit the lantern and went out the back door and opened the meat house door. There wasn’t a thing there. They stole the entire hog, every bit of it. Took it all.

03:09

Mae: Tell about the hog and your mother and the dog that caught the hog.

Damon: Oh, no, Mae.

Mae: Oh, yeah, tell her about that and then the other one about Denvil working at school…do that and the other….and about your Grandma Mullins that went sangin’ [ginseng hunting], and all that.

Mike: That one is too long. We will get it later.

Damon: The time the people stole the hog, that was end of the hog stuff. We didn’t have any more hogs. Not for that winter.

Feeding hog; Bertha inadvertently “riding” it—circa 1935

Bertha “riding the hog”, duplicate story—circa 1935

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: Back in those days and times, you didn’t keep you hogs on the farm and feed them through the summer. You put them out in the woods. They would eat off the mask [mast] in the woods: acorns, hickory nuts, and all that sort of thing. But you had to go out and feed them every so often, or they would go wild. So, we went out. It was mine and Mom’s time to go out and check the hogs. So, she took a bucket of corn, there was so much corn. We had a big ole collie dog. He went with us

So, the big mother hog, the big sow hog had a bell on. We could very faintly hear that bell, and we kept going closer and closer. As we got to it, that big ole hog had its front leg through that bell collar. It was just walking on three legs, and this leg was through that collar someway. It couldn’t get its leg out of that collar. Right up on the side of the mountain. So, Mom called the dog and said for him to catch that hog and hold it. Well, he really knew how to catch the hog. It would catch it and lay it right down on the ground, see, and hold it. He would catch it right in the mouth [Damon was using hand gestures to show Mike how] He would put it right down on the ground, and it would squeal and carry on and everything else, but it couldn’t move. It couldn’t get up.

So, Mom jumped on top of the hog, straddled the hog trying to get that bell collar loose, see. And then the dog let the hog loose. Down the mountain went Mom and the hog. She couldn’t get off and the hog…brush about beat her to death, see. The hog was just running on three legs. And boy she got drug off it after a while. We got on down the hill, and she called the dog and told it to catch it again. He caught it that time. She really laid that dog out good. She said, “I mean for you to hold that hog.” And he held it that time and she got that bell collar loose and got its foot out, see, and put it back on. We got almost home on our journey back to the house when she said, “Now you aren’t going to tell your dad about that are you?” I said, “No way!”

[So much laughing!!] But he said he knew it somehow.

02:45

Mae: Wasn’t there something about a snake…a snake that you and her were out one time…that you told me. And she did something…?

-

Mike: Now is that the same dog that took care of sheep and so forth?

Damon: And the hogs. We went out in the woods one time and caught a big hog. It was our hog, it wasn’t a wild hog. It had a bell on it so you could find it…big hog. That hog had run its leg through the bell collar. And it’s got that thing, what do you call it on a hog’s leg? It had gotten it through the bell collar, see, and was hanging up on it. That old hog was walking on three legs. Couldn’t get that leg out of the bell collar. So, we got up to it and Mom said, “Catch the hog, catch that hog!” So of course, the hog was just hobbling on three legs, it was no chore to catch. He just caught it, and it fell right down. So, Mom run up and got to a straddling the hog. She started to unbuckle the collar, and the dog turned the hog loose. And the down the hill it went, with her on top of it. She couldn’t get off. It run through the laurel patch; about killed her running through that brush. Finally, she got off, and the hog run off about as far as the road out there. And we got down that that time. I was just real little; I was just a little fella. Boy, she told that dog this time, “Catch that dog and hold it!” And that old dog when I got down there had that hog right by the mouth, just like that. Had its head right down in the ground and held it right there until she unbuckled that bell collar. Got its foot out of it, got off that hog and said, “Turn it loose.” He turned it loose. Mom stood there a little bit; her face had two or three big scratches on it and her hair all torn up. She turned around and looked at me and she said, “You aren’t going to tell this are you?” Of course, I didn’t until I got home.

Caring for hogs in the wild; Damon without shoes, in snow; branding livestock—circa 1935

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: Well, when we left…you had to go every so often and feed your hogs to keep them from going wild. Had to keep a bell on them. Hogs would go wild if you didn’t feed them and care for them a little while. Now cattle wouldn’t, of course. But we went up to take care of and feed the hogs. When we left home, I guess maybe along November or something around that time of year. We were getting ready to get them hogs rounded up to bring them in. You had to take them off what you call the mask [mast], bring them in and corn feed them so that the meat would be…wouldn’t be too strong. We started out that morning and went up through the Herman Nelson farm and out little Stinnett Ridge and over on to what they call Big Stinnett. Wasn’t a house, didn’t pass nobody’s house, see. By the time we got over there, there was about 3 or 4 inches of snow on the ground. When we left that morning there was no snow.

Mike: What time of year was that?

Damon: Along about in November, up next to Thanksgiving. Unusual. We got up there on that old farm, old L. B. Wood’s place on Big Stinnett. And the only thing that was on it from one little, tiny house. I don’t know if it was a…I guess a chicken house of some kind, very small. Wasn’t big enough to stand up in. So, Denvil put me in that little old house, and he went on, found the hog and then did whatever chores had to be done.

Mike: So, they wandered away that far?

Damon: Well, we knew about where they were at, you see. They took them and put them in the wood and let them eat, to keep from having to feed them. And you lost a lot of hogs that way, but you…well, you lost a few anyway.

Mike: How old were you at that point?

Damon: Oh, gosh, I would have been five or six. I didn’t have any shoes. So, when he came back, instead up going back up that hill like we had come down, that ridge, we went right down the creek. And there’s a road that is in the creek and out of the creek. And that is called Big Stinnett. And we went right down to where Big Stinnett and Little Stinnett met—it wasn’t too far. Right in the very fork of that creek was a little old tiny house. Some woman lived there…I cannot think what her name was. But when I got to there, he left me. He said it was very plain to see that I couldn’t go on—I didn’t have any shoes. Snow was 6 inches deep by then, you see. So, I had to stay there with that old lady. Denvil went on home, and for some reason they did not come back for me for a day or two. But I think it was the next day they came back and brought the horse. Back in those days and times, you didn’t start wearing shoes until it was absolutely necessary. I went out that day without any shoes on. Probably didn’t have any, but anyway got caught in that snow, and he left me over there.

Mike: Did you go out to bring the hogs back?

Damon: No, what they really did…what their theory was in that hog business. See if you had ten head of hogs say, you couldn’t hardly raise enough feed to keep them all…not on the kind of farm we had. Just keep them all through the summer, and you cannot kill them in the summer because there was no refrigeration. No way to keep the meat, see. So, we would take the hogs out into the woods where there was good mask [mast] and put bells on the old hogs because they weren’t near as apt to go wild as the younger hogs. Then you went back to them every so often and feed them a little bit of corn. You did this and that to them to keep them.

Mike: You didn’t tie them up or anything?

Damon: No, just took them out there, and like I said sometimes you lost a few.

Mike: You probably didn’t brand them, wouldn’t have done any good anyway.

Damon: We had a brand. Everybody had a brand and our brand was…I can remember that. You cut the very end of their ears off, and it was called a smooth crop. And when we moved up there the farmers gave us our markings, two smooth crops. You cut both ears off. Where their ears went out sharp, just cut it off. A lot of them had a smooth crop and a swallow fork that was a V-cut out of the bottom of the ear. Everyone had a...I cannot remember all of them, but you cut the ends off the ear and then cut a V back in. All kinds of markings. Now the cattle they put the marking on them with an iron, you know.

Mike: Did you have cattle, too?

Damon: Yeah, but we never did have that many. We’d let the cattle run out some, but never let them wander off that far.

Mike: Did you have a milk cow?

Damon: Well, you couldn’t let a milk cow get wild...you have to keep them on the farm, see. And your younger cows wouldn’t survived like a hog would in the woods. See, hogs could survive, if you were in a real good place.

Hogs eating chestnuts; prep for slaughter—circa 1935

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: Of course, by that time I was old enough to remember there wasn’t very many chestnuts. Not like it used to be—chestnuts were on their way out. But they would find a big old snag, usually where a chestnut tree had died. A bunch of sprouts would come up around there, and they would have chestnuts on them. There was still a lot of chestnuts in the woods then. And them old hogs would eat those things until they just laid down and eat them. I have seen them lay down and eat them chestnuts and they would just run out of their mouth. They liked them so well. And of course, hickory nuts, acorns, and stuff. But then if you killed a hog, butchered a hog, where it had been in the wood like that, they called wild mask [mast]. Then their meat was strong. The meat would be wild and strong. So, you keep on them hogs. You went up and checked on them and fed them a little bit. Then along about the time of year you would start bringing them in, putting them in the hog pen or barn a lot. You would start with the ones you were going to mark for slaughter. You would start feeding them corn (oats or corn), but mostly corn, of course. And that would sweeten the meat. And when they begin to gain. I didn’t know all about that, but they said you had to get the hog on the mend. You had their weight goin’ up, then you killed or butchered it.

Eating meat in the summertime—circa 1935

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Mike: I can understand hogs in the wintertime and taking care of food, but what did you do during the summertime? Did you hunt?

Damon: Oh yeah! But….

Mike: So, you didn’t eat a lot of meat in the summer?

Damon: No, you did not eat a lot of meat in the summer! The only thing you could eat in the summer was something you could kill and eat it all at one time. Like a…I can remember Daddy killing a little old mutton a time or two. Sheep, but there wasn’t anybody that liked them. Did you ever eat a mutton?

Mike: Yeah, I kinda like some lamb.

Hunting small game; deer was scarce; deer re-population effort—circa 1935

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: [Chuckling!] There might be some of it, but there was never a lot of lamb that I liked. But you could kill a chicken or something. And then of course hunting wasn’t good in the summer. You had to wait until fall for even your wild hunting. That is when the squirrels raised their little one and turkeys hatched out their…if you killed a turkey, it would be…. Have you heard of poorer than Job’s turkey? And then another thing I will tell you back in those days: squirrel population was heavy. Rabbits were heavy. But you hardly ever, ever seen a deer. Why a deer was almost unbelievable, seeing a deer then. I guess they killed them all out, I don’t know what happened to them. But it happened before I was old enough to remember. I can remember they talked about when the Legg’s, around Bickmore and Fola, bought some deer in. Conservation provided them with, I believe they said eight deer. They put two here and two there, and they got the deer started in that country. And then they did the same thing over all the other parts of the country. And of course, now the deer are so bad you cannot farm for them. Mae’s sister lives up there in Clay Country, and she cannot even raise a garden for the deer. They eat it up as fast as it comes up through the ground. Eats up her garden. We went over there one time into Clay County, and the part that we was in, they said that the biggest complaint about deer eating up their crops. See you could go in and file a complaint with the…get paid for the crops that the deer eat. But out in that section, every tree had a sign nailed on it said, “No Hunting.” They didn’t want you killing the deer, see. They wanted to be paid for the crops the deer eat up. It was pretty obvious that they hadn’t planted anything to start with. It beat all I ever seen.

Mike: It is one of those things that you over protect, and that is what they are doing in a lot of these cases now.

Damon: I never thought about deer getting that big, though, like it is here now. Three walked across our yard the other day. Back over in them places where they garden, back in Clay Country where they garden for a living. They garden for the benefit of the garden. We garden just to have good fresh vegetables. We didn’t…if you worked every day, you didn’t garden just because you had to, but because you wanted to. But there, back then, there was people that gardened because they had to make your meal come out of it.

13:15

Mike: Eat to live, right? What else was it she said? What was the other story she was talking about?

Damon: I don’t remember.

Making molasses using a horse; dog tackling the horse—circa 1936

Was the dog in this story the same one as in this 1940’s Bentree photo? “Old Billy Dog” was his name. Damon called the dog in this story (and the hog story) by the name “Bill”. It could have been the same dog, or maybe this one was the next generation of dogs named Bill.

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Damon: No, it was the horse, making the molasses?

Mae: Yep.

Damon: When we lived down on the farm, we had this old dog. It was a big dog. But, of course, we thought the dog could do anything, you know. Anything you asked it, and it usually did it. He’d catch a chicken or catch just about anything you wanted. He would go out and get the cows and bring them in, to milk them. The dog’s name was Bill.

Mike: What kind of dog was it?

Damon: Just a big old collie. So, we were making molasses. You know how you put the horses in the molasses mill and they go around and around and around and grind the cane into juice, which went to the molasses pan. And we were…all the kids were down in the field hitting cane. Cutting heads out of it—it is a big pod of seed. You cut the heads out to feed the chickens in the winter.

Mike: Was this over on Buffalo?

Damon: Yes, over on Buffalo, on the farm. So, in the process of…every so often they would change horses in that process of grinding the cane. Because it was a tiresome job going around, and around, and around.

Mike: Where was it? It wasn’t at your farm was it?

Damon: Yeah, we owned the mill and everything. Right on our farm. Big bottom there. So, it came time to change the horse and put the other horse in. It was real mean, and when they changed it out, it broke loose from the person that was doing the changing. Taking it out and putting the other horse in. It just reared up and struck right down the field toward us just as hard as it could come. Had this harness on. Mom was standing there with a pan, and she couldn’t think of anything to do but holler for that dog [named Bill], see, to catch that horse. And it just broke into a run…the dog as it passed the horse up. It could run faster than the horse. When it got up to it, he jumped up and caught it right in the mouth. Took its head right down between its legs. I can remember, sitting in there in that cane with that horse’s feet all up way in the air. That old horse hit the ground and didn’t get up for a long time. Liked to have killed it. You would not think it was possible…

Mike: Smart enough to do that!

Damon: Yeah, caught that horse, knowed the only place to catch it was right in the mouth. No use to catch it by the leg or nothing. And when that dog passed it, he come up and caught it right in the mouth like. When it went down, that horse’s head went right down with it.

Denvil & Damon move big hog from Buffalo Creek farm to Dundon—April 1, 1937

To hear Damon tell this story, click the audio button below. If you want to see the transcription, click on + sign in the “accordion” bar below it.

-

Mike: Really, what I want you to tell me about was some of the stories that you have told me over the years. Stories like growing up over in Clay.

Damon: All those stories about growing up on Clay--you try to forget ‘em!

I told you about the one when we moved away from the roughs of Buffalo Creek: when the family moved away and left Denvil and me there to take the last...we had the one hog to move.... It’d have been (1937). I guess I'd have been nine years old. Denvil would have been about five years older than me (so what would that make him?) he wouldn't have been more than 14 would he? We stayed there and had an old BIG hog to move. And we had to build a crate on the sled.

Mike: You didn't have a truck or anything like that?

Damon: Oh! The truck would have scared us to death.

Dianne: So how did your dad get over there?

Damon: They moved--they took all the furniture to the railroad head and put it on the railroad...on a boxcar and moved out to Dundon, and the truck picked them up and moved them to Bentree. But the hog had to be moved separately, see. Ahh, it was a big hog. It must have been--gosh it must have been a three- or four-hundred pound hog. Big one; big ole hog. So, we built the box on the sled--that crate to put it in. Then we had to build it in the door of the barn, see, because we couldn't move the sled. The only thing we had to build it with was a hatchet--we didn't even have a saw. When we got the crate built, then we got in the barn and got the hog into the crate that way see. It went up to the door and then went up in that crate. Then we nailed the boards across it until it couldn't get out. We left there with the horse hooked to the sled and took it all the way out on the ridge to where we could get to the truck and then of course my dad and Elmer came back. Elmer Dobenspeck came by and picked the hog up on the truck. Denvil took the horse back to the farm--just turned it loose. We had sold the farm and the horse, and everything went with it see.

The family, if I remember right, had left on Friday morning early. And they had a big coal stove, and you didn't build no fire and stove to cook. You didn't have no refrigerator--you didn't eat no leftovers. So, when they got up and moved, we moved the stove without building a fire. Because you couldn't put the stove on the sled and move it to the railroad. And there was no breakfast; and when lunch time come there was no dinner and when supper time come.... There was just the two of us there working on that hog crate. It was in April; I believe we moved on the first day of April. I can't remember for sure.

Mike: How did you move that sled?

Damon: The horse pulled the sled.

Mike: There wasn't any snow on the ground?

Damon: Oh no, but it had runners. It was built with these sleds that you could pull on dry ground with a horse. Of course, there was a lot of friction--a lot of pulling, but that's why they did it. They put what they called hatch souls on the sled. And when they wore off, you put another one on it, see. It would pull up on the rocks, wear out, you put them on a wooden pole. The old sled was heavy, and you put something like a hog on it--it was something to pull, but that's way that you went, see. But getting back to my story about eatin'. By Friday evening we were really getting desperate for something to eat.

Mike: They hadn't left you anything to eat?

Damon: Nooo. Never left a thing. And we hadn't eaten since I guess Thursday evening. So, we still had Saturday (Friday night and Saturday). And then that old house: they wasn't even a throw rug; there wasn't.... When you get a house completely empty, there was nothing in it, not a thing, but a fireplace. The only thing you did was lay on the floor, the hearth of a fireplace.

Denvil took the hatchet (we had one hatchet). It was in the spring of the year you know the sap coming up. He went around to the end of the field and cut some bark off a birch tree. A birch tree has a real thick pith in it when the sap's coming up. We scraped it off, you could eat it. It wasn't filling, but you could eat some of the bark. And then Saturday morning come, and we were still hungry. Then we was all day getting that sled out on what we call Tripp Ridge. We had to go down cross the creek and up the hill to get to the top the hill. Then Daddy and Elmer come there, along up in the evening, and backed up to the bank. And we finally got that hog in the truck. Denvil had taken the old horse back to the farm and took the harness off it and just turned it loose in the field.

Mike: Did you go back with him?

Damon: No, I stayed there with the hog, while he went back and turned to horse lose in the field. Looking at our age, there wasn't a whole lot I could do to help him. Now, I'd like to see a 14-year-old boy now build a crate and put a hog in it and take it out on that road.

Mike: He took the horse back and then came back and met you there?

Damon: Yeah, it was a pretty good little jump--you know you had to go out that ridge, then you went down the hill and made these back turns down that hill. Until you got to the railroad track, crossed the railroad track, crossed the Creek, and over into the ole homeplace. And then you had to go all the way up through it, out to the old barn we had (I didn't go with him, but I'm sure he did go up there and unharness the horse. Kind of hard for someone no bigger than that, you know, to harness and unharness a horse).